Post contributed by Dr Lisanne Braat, European Space Agency (ESA)

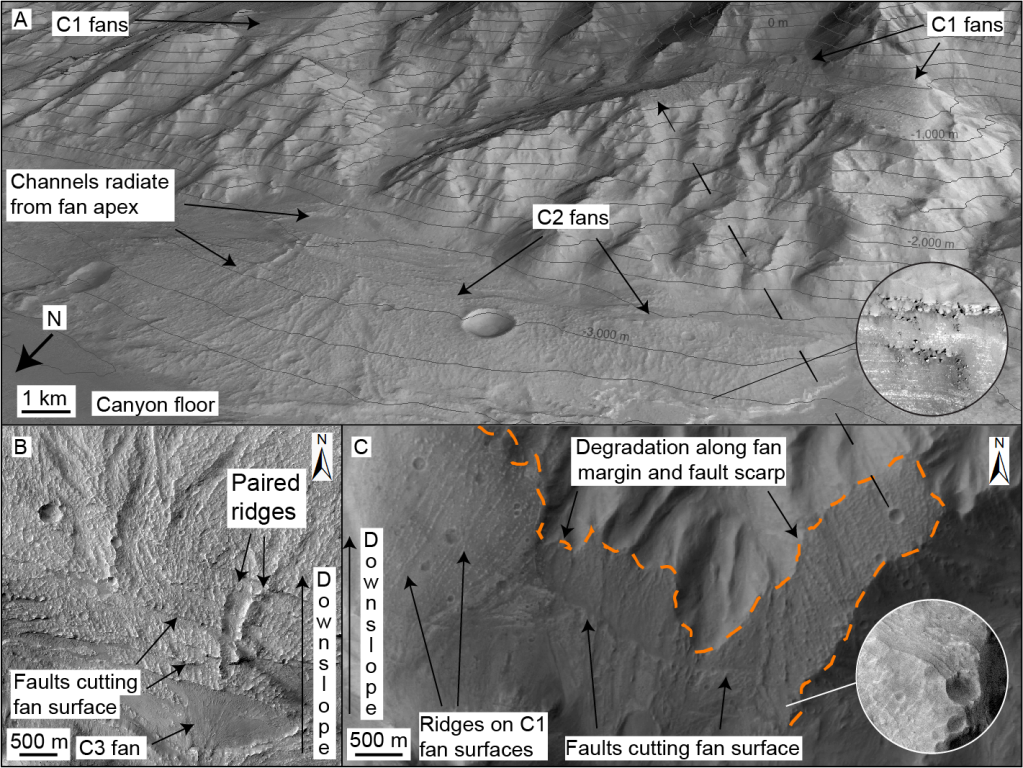

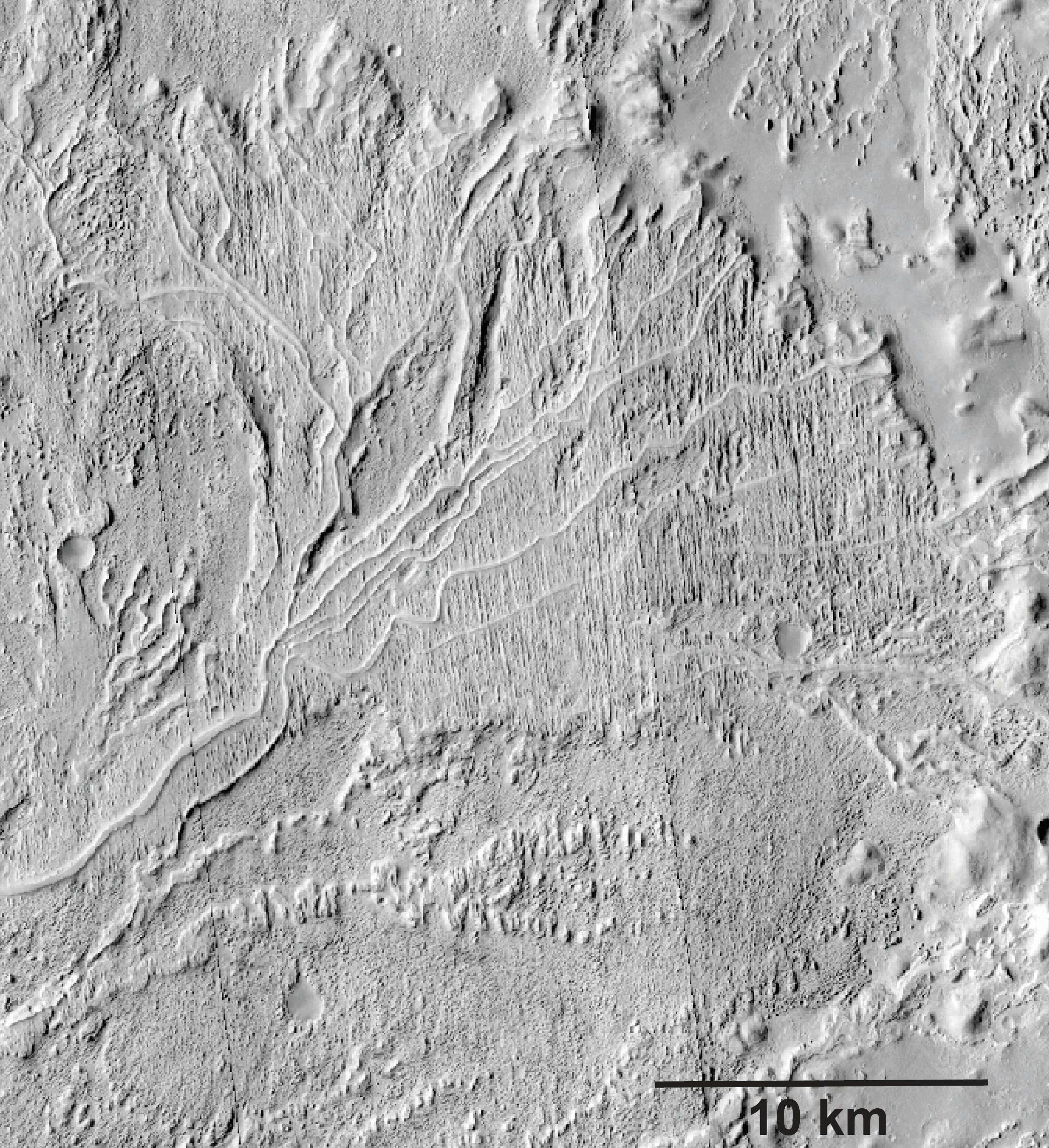

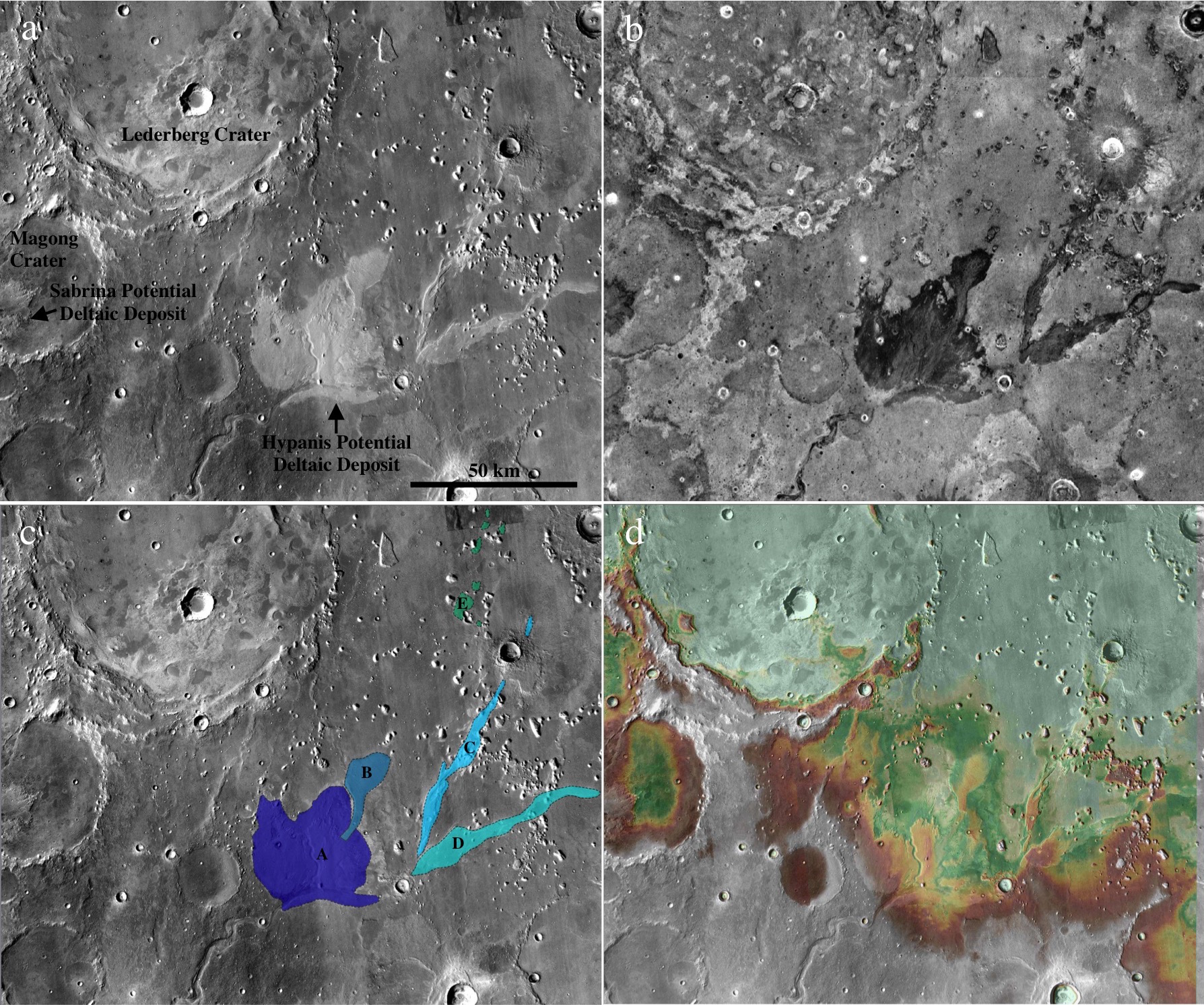

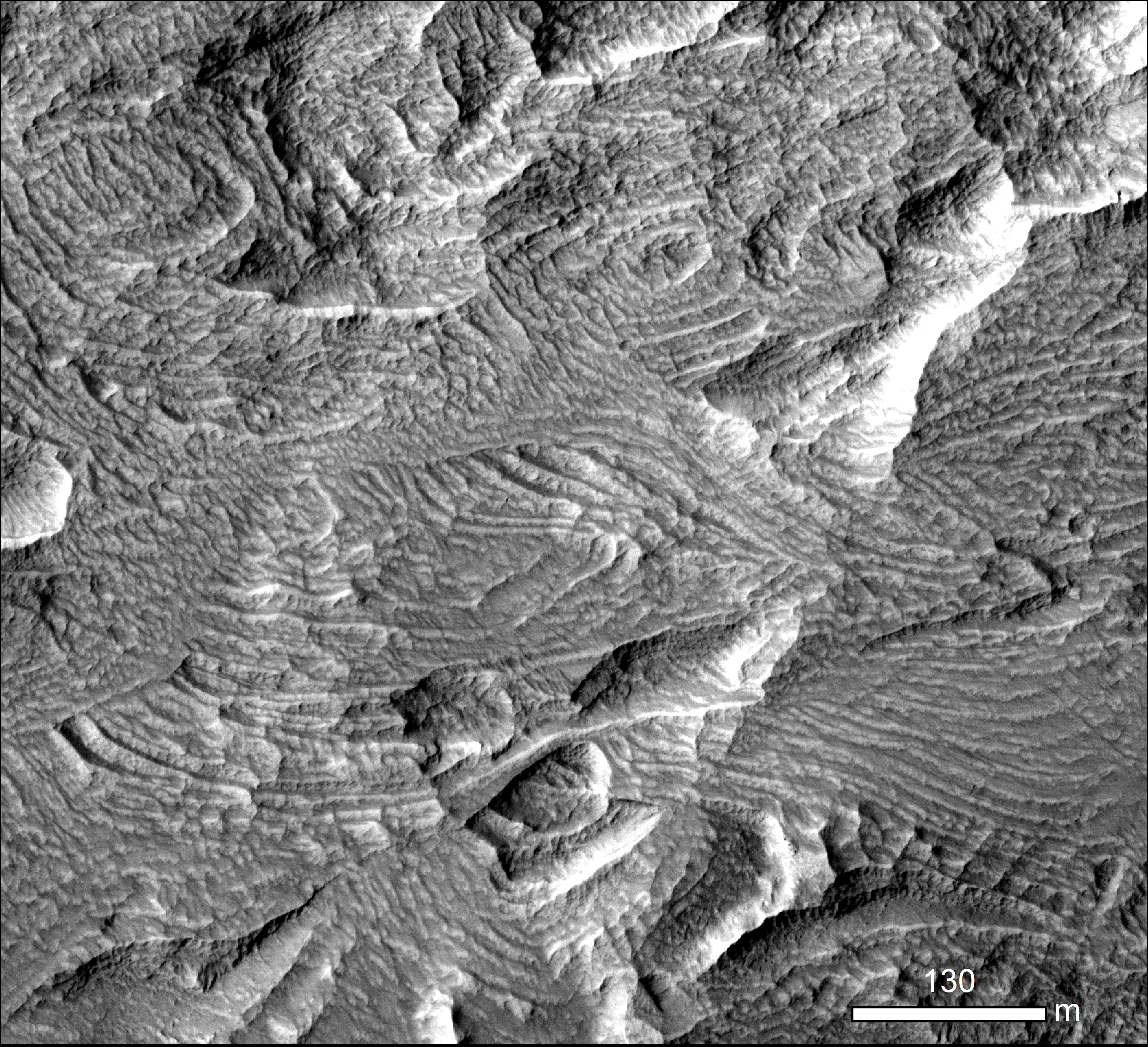

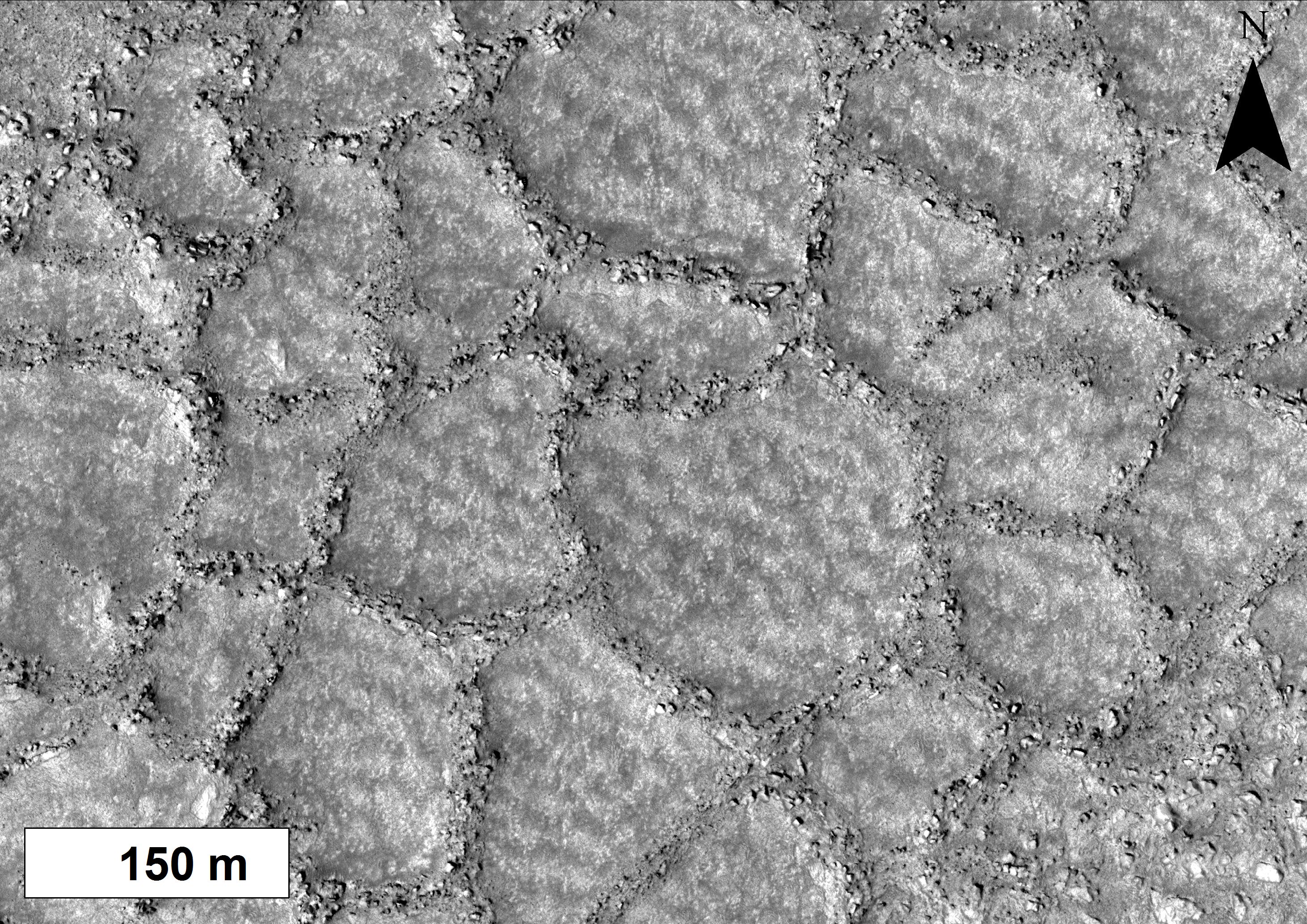

Deltas form when a river flows into a standing body of water. When the flow decelerates the sediment carried by the river settles and forms the delta. On Earth we have numerous active deltas where rivers meet lakes, seas, and oceans. Examples of Earth’s deltas can be seen on the left side of Image 1. On Mars, we observe many remnants of ancient deltas that are no longer active (shown on the right side of Image 1), such as the delta in Jezero Crater where the Perseverance rover currently explores. Preserved sediment deposits in these Martian deltas provide valuable insights into past processes on the planet’s surface and the presence of water. To better understand these landforms on Mars, we rely on knowledge gained from active delta systems on Earth. However, is it fair to do so when the gravity on Mars is much lower? How does gravity affect sediment transport and delta morphology?

Image 1: Animated GIF comparing Deltas on Earth and Mars. Left, examples of active deltas on Earth (source: Landsat). Right, examples of preserved ancient deltas on Mars (source: JMARS composite of CTX Global Mosaic, Murray Lab, and HRSC MOLA Blended DEM 200m v2).

(more…)