Post contributed by Ernst Hauber and Lida Fanara, Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany.

Mars is an active planet, and several processes are currently shaping its surface. Among those, gravity-driven mass wasting produces surface changes that can be quantified in image data acquired before and after discrete events. As such changes are typically small in their spatial dimensions, the prime dataset to recognize them are pairs of HiRISE images (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment; McEwen et al., 2007), with scales of ~25-50 cm/px. The manual identification of surface changes in these huge images (a single HiRISE image can have a size of several Gigabytes) is challenging, however, and requires significant efforts. In order to circumvent this massive demand on human resources while yet taking advantage of all images, automated methods need to be developed. Here we show an example of such methods which was applied to ice block falls at a steep cliff in Mars` north polar region.

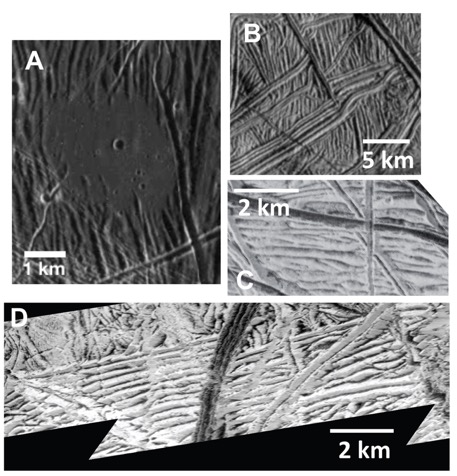

Image 1: Block fall at a scarp on the north polar region of Mars near 83.796°N and 236.088°E. (a) «before» image acquired at 06 May 2014 (HiRISE image ESP_036453_2640). (b) «after» image acquired at 25 December 2019, showing a cluster of blocks that was displaced from the scarp to the right (east) (ESP_062866_2640). North is up in both images, scale bar is 100 m.